Thanks to Kristen Lamb for pointing me to this one in her "Five Mistakes KILLING self-published Authors" column. I think she overemphasizes social media a bit, but otherwise her columns are usually right on.

Thursday, December 26, 2013

Sunday, December 8, 2013

SF Canada Bookstore

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Common Mistake #3: Physical Descriptions in Place of Characterization

There are three problems with providing too much physical description of characters (and to some extent, of settings).

First, timing. Beginning authors often feel they have to provide the character's appearance immediately upon that character's initial entrance. There is certainly a logic to that, but then what one often gets is expository lump right in the middle of what is supposed to be an action scene. Say an assassin jumps out at our hero: if the author feels compelled to provide a detailed description of what the killer looks like, then instead of the rapid pace of swordplay, gun fire or fisticuffs, the story comes to a complete standstill while we are briefed on disheveled hair, wild eyes, rumpled suit, and so on down to the shoelaces. Interesting as all of this might be, it is less relevant and compelling then the fact the individual in question is trying to kill the viewpoint character.

When police try to debrief an incident, for example, the witnesses are often hard pressed to identify their assailant's hair and eye color and height and so on because their attention was pretty much focused on the fact that they were being assaulted. In the heat of the moment, eye color is pretty far down the list of what people notice; so the reader won't really notice its absence either, if the writer provides sufficient action. What the reader will notice is that description replaced action; that the action ground to an unexpected halt at the precise moment the author should have been building tension.

Second, although the author may have cast the character in a particular way, imposing that one specific actor/description on the reader is unnecessarily restrictive. Yes, the author may have worked hard to picture the scene s/he is trying to depict down to the specifics of hair and eye color, but contrary to the beginner's understanding of the process, the writer's job is not to reproduce that scene in the reader's brain exactly as the author originally pictured it. On the contrary, one wants a certain level of vagueness, of blank canvas, onto which the reader may project their own experiences and preferences. Just as a playwright has to allow for a certain amount of interpretation of the script by the director and actors, the writer has to leave room for the reader to bring something to the project.

For example, if the story features a bully, then it is far better if in the reader's mind that bully merges with that bastard down in accounting who is currently making their life miserable. Of course their conscious mind is not about to suffer any such confusion, since pretty sure guy in accounting is not in fact king of the space vampires, or whatever; but great fiction, like great opera, often bypasses the intellect and goes directly to the viscera, with people's emotions. The resonance between the writing and the reader's own experience may be disrupted, however, if one insists on establishing definitively that the guy in accounting is not the bully under discussion because the one in the book has red hair and blue eyes.

Or, to take an example from the other end of the emotional scale, if one is too precise in describing the love interest, one runs the risk of including a detail that is, for the reader, a deal breaker. "Electric blue eyes" are as likely to remind them of their ex as of their current lover. (It is the same reason why it seldom pays to be too explicit in sex scenes: if it doesn't happen to be the reader's kink, one is more likely to get an "eewww!" than a sale.)

So why go there? If the writer insists on determining every microscopic detail of the experience for the reader because that happened to be how the writer pictured the scene, then it's not about trying to be precise, it's about being a control freak. If one wants to build readership, one has to give up some control so the reader can take some ownership of the reading experience. If one wants readers to recommend the book to their friends, then the reader has to come to think of it as one of their books.

Third, the author of course believes one breathes life into a character by providing all this detail; but in fact it often has the opposite effect: by lavishing attention on the physical description, the author is to that same degree likely to skimp on actual characterization. Eye color does not a character make, because one can randomly (re)assign hair and eye color and not change the character in any fundamental way. (Well, unless these things have special significance in this particular SF&F world, that grey eyes indicates elvish ancestry or some such...). Characters are generally memorable because of their actions, motivations, attitudes, strengths, flaws—in short their personalities— rather than eye or hair color. If one's character notes are all about physical appearance, then you're doing it wrong.

As we frequently reassure each other, it's not appearance that counts, but what's inside.

Which is not to suggest that one should never provide any detail of appearance or setting; only that one needs to ensure these details are inserted when timely and relevant; that they don't occur as a disruption of the narrative, or in overwhelming quantity (see previous column, "Common Mistakes #2: Less is More).

[Cartoon stolen from Bliss by Harry Bliss Sept 22, 2015)

Friday, November 15, 2013

Advice to Redacted

-

Worry more about writing good stories than getting published. The publishing industry is just the minotaur in the middle of the maze: the challenge at the end. You still have to get there. You still have to wander the maze in order to fight the monster.

- Don’t chase trends—let trends chase you.

- I’ve been hearing these nasty horror stories about writers going hungry, being unable to find jobs...

I think he's asking, "How do I make a living as a writer?" And not just a living, but really, "How do I obtain the lifestyle to which I aspire as a successful writer?"

The answer to "how do I become a writer" is very simple: one writes stuff. If one has the least talent and invests the usual 10,000 hours of continuous study and effort, one can likely even manage to become a decent writer. Perhaps with persistence, a published writer. Taking Windig's advice would probably help in becoming a published writer.

The answer to "how do I make a good living as a writer" is, however, entirely different: you can't.

I know just about all 200 or so of the SF writers in Canada, and out of that number, I'd estimate that only 3 or 4—so call it 2%—actually make a decent living as writers. Even Sawyer—unquestionably the best known of Canadian SF writers—recently remarked that he couldn't make a living by writing alone: his speaking engagements are a necessary supplement. (Sawyer is a fabulous speaker, by the way, which cannot be said of many writers. It is not a sideline that most writers could avail themselves.) I could name another 10 or so whose major source of income is writing, but their lifestyle is strictly hand-to-mouth. For example, I remember one of them —one of the better ones—exclaiming over a minor winfall that afforded her the luxury of buying box of tea large enough to last her a month. I strongly suspect that this would be the sort of 'horror stories' to which Redacted was referring. Everyone else basically had day jobs to support themselves. Of course, many of these day jobs involved working as writers—speech writers, technical writers, journalists, copy editors, staff writers, English teachers, and so on—but still, 9-5 jobs working for other people.

So, people who pursue writing as a career in the expectation of being one of the 2% or so of writers who are actually able to make a living as novelists are basically deluding themselves. If one's motivation for writing is to acquire the writer's lifestyle, then one had better understand that that life is about earning the occasional box of tea, not the glamorous life of the best seller. The chances of making it as a big time writer are about the same as a random hockey-playing kid making it to the NHL. Obviously, some do, but um, one doesn't plan one's life around that expectation.

[Having said that, though, my colleague the career counsellor tells the story of a student who explained to him that he didn't require career counselling because he had already decided that he was going to play for the NHL. My colleague insisted that the student develop a 'backup plan' for his education, "just in case" that didn't work out (*snicker* *snicker*); but the student in fact went on to become a huge hockey star, much to my colleague's eternal chagrin. So far be if from me to tell anyone that it is impossible for them to make it to the NHL or the Times bestseller list; I'm just saying wait until after your first $100,000 advance to quit your day job.]

I really have two points here. First, becoming a writer should not be confused with becoming a full-time professional. There are lots of opportunities for writers; indeed, thanks to new self-publishing technologies, there is now no excuse for anyone not to become a writer.

There has been some fascination in social media lately, for example, with the statistic that in Iceland, one person in ten has a novel to their credit. People seem surprised and impressed by this statistic, but I think that response is based on confusing "has written a novel" with "is a full-time writer". Because I'm pretty sure that is not the case. I very much doubt if the market for Icelandic literature is large enough to feed very many writers; nor that much Icelandic literature gets translated (or written in English) to penetrate the international market. What that one in ten figure is really telling us is that in Iceland, people write (and finish and circulate) their novel, even knowing that there isn't any money in it.

Being an editor, I have the (undoubtedly annoying) habit of asking people "written any good books lately?" as a variant on the usual conversational gambit of asking people what they have read recently. But here's the thing: probably one in five answer that they have indeed written a novel (or at least started one), now safely tucked away in their dresser's bottom drawer. Granted that I am probably dealing with a biased sample given the sort of people I am likely to run into, I don't think it is too much of a reach to suggest that perhaps one in ten Canadians have also written (or started) a novel. The difference between Canadians and Icelanders, then, is that Icelanders then go on to share their novel in the reasonable expectation that they have something to contribute to the body of Icelandic literature; whereas Canadians do not think in those terms at all. Quite aside from the fact that we are intimidated by a North American market that swamps any sense of a Canadian canon to which our work may contribute, we tend not to see literature as a conversation between writers, or between writers and readers, but as a way to make money. I very seldom hear people ask, "do you think anyone would be interested in reading my book"; instead they ask me, "will anyone buy it?" It is a subtle but significant difference. If a Canadian cannot believe s/he can make it as a professional writer, the book(s) go in the bottom drawer. But that's crazy. Just because you can't make the NFL team, doesn't mean you and a bunch of the guys can't get in some ice time. If it is okay to be an accountant during the day, and play Hockey Thursday nights in your local league, why isn't it okay to be an amateur writer? But in our capitalist mindset, if a book doesn't sell well enough to pay out on all the hours it took to write it—at an hourly rate equivalent to or exceeding our day-job rate—then it must be considered a failure.

This is astonishingly wrong-headed.

Contrary to the position of capitalist ideologues, market forces are not the only measure of worth. Indeed, Stephen Meyer and David Brown and E. L. James and a host of others are pretty compelling evidence that market forces are a very long way from the best measure of quality.

Don't get me wrong: I have nothing against making money from writing, and wish every writer the best of luck. But the expectation that one should be able to make a full-time living from writing is well, unrealistic. Poets and origami artists have had to face the fact that there are very few full time positions for poets and paperfolders, but thankfully poetry and origami have not died out.

Second, Redacted wants to know the secret of becoming a full-time author because "economics isn't for him". This reminds me of an acquaintance who patiently explained that she had had to quit her job "because I'm not like other people. I cannot tolerate the restrictions of a 9-5 job. As an artiste, I have to have an outlet for my creativity. I have to write!" One got the strong impression that she believed herself surrounded by worker bees who were perfectly content working 9-5 jobs, who didn't get just as frustrated with long hours, annoying coworkers/bosses, and mind-numbing routine as she. In other words, she was a spoilt, self-entitled idiot. There is nothing wrong with Redacted asking how one achieves one's dream job; but it is important to recognize that that is one's dream job, not one to which one is inherently entitled. I note, for example, that my aforementioned acquaintance never in the thirty years since produced a single short story, let alone a novel, while plenty of the worker bees she disdained managed to hold down two jobs, raise a family and still knock out an impressive novel or two.

Or, to put it another way, the complaint that one can no longer make a living as a novelist is kind of a first world problem. There are like a billion people on this planet who can't access clean water, so I find it hard to get worked up over the fact that one can't always quit one's day job to indulge oneself in full time writing.

Again, don't get me wrong: there is nothing wrong with aspiring to become a full-time novelist; but one does not generally get there by starting as a full-time novelist. One gets there by writing. After work, after the kids are in bed, and if they are very lucky, a little bit extra during NaNoWriMo. Once one has had some critical and financial success, one might consider whether quitting the day job to free up more time for writing is a practical option; starting from the assumption that that the world owes one a living as a wordsmith is the road to disappointment.

This is not a popular position. When I say things like this, aspiring writers tend to hear "you're telling me I can never be a writer, and I should give up"; which is, of course, pretty much the exact opposite of what I am actually arguing. I'm an educator as well as a development editor, so I pretty much believe that given sufficient commitment anyone can become a competent writer; and that almost all of my clients could become proficient or brilliant writers. I'm just arguing that becoming a writer should not be confused with becoming a best seller. That aiming at the best seller market my actually demand that you become a worse writer than you are now. That selling your vision, your voice to break into the American mass market may be a really bad goal. What I am arguing is that maybe it is okay to be a part-time writer, to write for an hour or two each evening, rather than all day. (As it happens, most full-time writers only write for part of the day anyway, the rest being spent on marketing and recharging their creative energies, but that's a topic for another column.)

Let me give you an example: H. A. Hargreaves was a university English professor who devoted roughly one week every second year to writing short stories. But over his career he produced two short story collections, North by 2000+ and Growing up Bronx which represents a respectable output. Indeed, I have argued elsewhere that the stories in North by 2000+ have had a profound influence on Canadian SF. Hargreaves never expected nor made a living from his writing, but he nevertheless made a truly significant contribution to Canadian culture and became a hugely important part of the conversation with other writers, critics and readers about what makes writing Canadian.

It is not necessary to be a professional writer to count yourself a writer. Writing doesn't have to be a career. Authors who disdain 'amateur' writers are not just pompous, they are suffering from false consciousness: they have been duped into believing that schooling is about job training rather than education; that culture is only valid if it is an industry; and that the only measure of success is income. Instead, they should be celebrating the opportunities to join with all writers and readers (most readers these days being other writers) in the conversation that is Canadian culture. They need to recognize themselves as a 'class' and develop the class consciousness that rejects the divide and conquer logic of professional vs amateur. They need to embrace readers and beginning writers and self-published writers as their brothers and allies in lobbying for more recognition of the arts. They need to become, in Gramsci's terms, the organic intellectuals that are the vanguard of the revolution to—

Oops, sorry. Getting carried away there. Baby steps.

Write your novel, your stories. Strive to get better; strive to have something to say. Stop asking if you can make a living at this. Do it because you have something to say; because you were blessed with a muse; or simply because self-expression is more enjoyable for you than stamp collecting. If you ever get good enough to actually make significant amounts of money, well, bonus!

But if you're in it for the money and the lifestyle...have you considered buying lottery tickets as a more viable career option?

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo)

On planning: http://theaccidentalnovelist.wordpress.com/2012/10/12/weekend-workout-prepping-fo-nano-or-not/

On just going with the flow: http://theaccidentalnovelist.wordpress.com/2013/10/30/nanowrimo-2014-team-pantser/

I'm usually some combination of both. I often have an idea that has been perculating in my head for years, often decades, where I have daydreamed various scenes here and there while walking the dog or shoveling snow. So I have a general idea of what the novel is about, who the main characters are, and where the novel is going, but with really only fragments of scenes here and there and big gaps between. No real structure or outline. So NaNoWriMo is a chance to get what I have down on paper and to see if I can connect the dots. The end result is often very different than where I started, and I occasionally write myself into corners by writing blindly; but on the other hand, I often generate new scenes and characters I would never have thought of if I were using a disciplined outline. By writing myself into corners, I force the protagonist to come up with a way to extricate himself, which I would never have thought of in an outline, because I would have known better than place him in that corner in the first place, if I had had a plan. So my hero is much cleverer and a much faster talker than he would have been otherwise.

It's true that I have had to cut whole sections of the novel that haven't worked out, because by going in that direction I precluded something that I realized had to come in later for the novel to work, or that went against character, or otherwise didn't work out. But at 2000 words a day, I could afford to dump a ten or twelve page section and try again; whereas if an outline had called for that scene and it had taken me a month to write, I would be far more reluctant to give up on it, persisting to the point of such frustration that I might be tempted to abandon the whole project as undoable.

I'm also quite a slow writer and tend to write longish novels, so has taken me two to three NaNoWriMo to get first complete draft. Now is the time for outlining, to make sure that I haven't lost track of any of the bits I started with (I lost two of the main characters there for awhile, and had to go back an account for their absence) and that everything works logically. I was actually surprised to find that my subconcious had indeed planted many of the clues in early chapters to foreshadow the unfolding of the mystery, even though I had had no idea what that mystery was when I set out. So having a first draft, I can go back and get a plan for the revision; I can use what my subconscious provided as raw data and use the resulting outline to tighten everything up so that the structure really works.

Or at least, that's the plan. Come Friday I start work on my new novel (opening scene clearly in my head, though getting that scene down on paper is a whole other thing) so will have to see how far on the back burner the previous novel gets pushed.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Opening Sentence (Non-Fiction)

Friday, October 18, 2013

Buy Your Favorite Author a Latte

Reading a "review" of Five River's new Dave Duncan release on Amazon, I was taken aback by someone rating the book was one star because it was priced at $4 for a novella. The reviewer made it clear that he hadn't actually read the book, but was merely incensed at the price.

Leaving aside the obvious disservice of erroneously giving a one star quality rating when really the complaint is about the cost rather then the quality of the writing, I simply don't get the attitude that authors, editors, cover artists and publishers should all work for free. An unfortunate result, perhaps, of the burgeoning self-publishing industry where substandard authors—desperate for an audience—price their books at $0.99, or give it away free in hopes of attracting readers. I understand the principle of giving away the first book in a series in hopes of attracting sales to more recently issued volumes in the series, but what we're seeing is a race to the bottom.

Promotional giveaways notwithstanding, in general you get what you pay for.

Or to put it another way, I don't get why some people seem to believe that writing should be sold by the pound or linear foot. Fifty Shades of Grey is 528 pages long but does that really make it worth a cover price three times higher than Duncan's novella? To me, it should be the other way around: Duncan's books are the ones worth reading. Once you get past the actual paper costs (not relevant in digital books), there is no reason to assume that longer should necessarily cost more, or that shorter needs be massively discounted, to the point where writing and publishing are no longer economical.

I think a novella by Dave Duncan is worth $4. I pay more for my morning latte. Dave's novella took considerably longer to read than a latte to drink, and the pleasure of that reading lasted longer yet.

If the cover of the latest issue of, say, Fantasy and Science Fiction Magazine included a short story by Dave Duncan, I would have immediately paid $6 for the magazine to get that story. Indeed, I did renew my subscription to NeoOpsis Magazine awhile back because they had a Dave Duncan short story in the latest issue. So why is it that some people suddenly find $4 an outrageous price for a novella when its a standalone package?

I love Duncan's stuff, and I want him to write more of it, so am willing to pay him to go do that. Specifically, to write the next two books in this series. A consumer will end up paying $11.95 for all three novellas in the series. And you know what? I'm okay with paying $11.95 for a Duncan novel or story collection. His books are worth at least that much of my coffee money.

So here's the thing: if you ran into your favorite author at the mall, wouldn't you offer to buy him a latte if you got to sit and listen to him tell a story for an hour?

Monday, September 23, 2013

Common Mistakes #2: Less is More

Or, to put it another way, while it might have taken the writer three days to shape that description of the forest, and so had time to savor each carefully crafted image, the reader is going past at a 1,000 words a minute. Okay, maybe if you're Proust or James Joyce, readers will slow down for you, but, um, you're not. Not yet, anyway. So less is more. Out of the ten images you've come up with, pick the best one; prune the rest. This will usually make the scene—and your writing—leaner, tighter and so much better.

Same with metaphors, jokes, and even surplus characters. Had a manuscript across my desk yesterday where a writer used essentially the same line twice within three pages. It was funny and it built up the speaker's character, but you can't get a laugh out of the same punchline twice in three pages; one of them has to go. Later that same day, I was reading a another manuscript where the author introduced several characters, spent time describing them, building up their personalities, but then didn't actually have them do anything in the story. They were just sort of there...except for one character who sat out the entire story in the barn, and so wasn't even there. Maybe save the barn character for another story.... Just because you thought of an image, or a metaphor or a character, or a funny line doesn't mean you have to use it. Keep to the point, keep things moving forward, and restrict yourself to your very best material.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Common Mistakes #1

Monday, September 2, 2013

SF Canada

World Fantasy Convention 2012 was hosted in Toronto, Ontario Nov. 1-4, where SF Canada members restated their 1992 corporate charter to approve continuance into the new Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act. Shown here wielding a ceremonial blade is Dr. Robert Runté from the University of Lethbridge, one of the founding members of SF Canada, along with current president Steve Stanton.

Self-Editing

Six Easy Tips for Self-Editing Your Fiction.

Not everyone can afford an editor, so knowing how to edit one's manuscript oneself is crucial. But Lamb also makes the point that even if one can afford a professional edit before self-publishing or submitting the manuscript to a traditional publisher, you get more for your money if you can edit out the obvious mistakes before hiring a professional:

- There are many editors who charge by the hour. If they're spending their time fixing blunders you could've easily repaired yourself, you're burning cash and time. Yet, correct these problems, and editors can more easily get to the meat of your novel. This means you will spend less money and get far higher value.

I was sufficiently impressed by this article that I followed it back to Lamb's personal blog which also turned out to be pretty good. Funny and insightful, even though I don't always agree. But enough to make the input useful. Check her out.

Saturday, August 3, 2013

Errors

Oops.

That, of course, is exactly the kind of error editors are supposed to catch. I hadn't. Worse, when I went to correct the error, had to be reminded by the author I'd also have to change "brother-in-law" to "son-in-law" throughout.

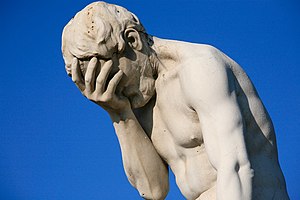

Face:Palm

Why I hadn't caught that, I'll never know. Lack of sleep, I suppose, or rushing, or my faith that this was one of those very few authors who didn't make mistakes. (Also, author's spouse is incredibly good copy editor, so usually submission is pretty clean before it leaves the author's hands.) But still, I'm pretty embarrassed.

Fortunately, we caught it before it went to layout (i.e., typesetting). Would like to think it would have been caught at the Galley stage anyway, but the sooner one can eliminate errors, the better.

Of course, mistakes are inevitable. If an editor claims they never let anything slip through, they're lying.

Why there are galleys. Even when editors catch mistakes--say, notice that the spelling of a minor character is different in different parts of the book--it often turns out that was the mistake: there were two different characters with similar names. You know? So authors have to be given opportunity to read through the book one last time before it goes to press. And even then, there are always things that slip through. Usually, right there, front and center, at any random page you first open the final published book. *Sigh*

The worst mistake I was (tangentially) involved in was back when I was working for the government as a Test Developer (i.e., test writer/editor). A Grade 12 Mathematics examination went out with one of the equations missing an exponent, which meant that there was no correct answer for that multiple-choice question. My boss was assigned to find out what went wrong, the implication being that heads were about to roll.

He traced the error back to the original manuscript, but the question wasn't why the author made a mistake (everybody makes mistakes) but why it wasn't caught in all the checks that were built into the process. The provincial exams were the most heavily reviewed and edited documents on Earth, so how did the error get through?

When my boss followed the trail of signatures, over 36 people had signed off on the document. 36 people. I was one of the Test Developers who had reviewed the test, but I pointed out that as a Social Studies guy, I had no clue about the actual math (hey, it was the advanced Grade 12 course. Calculus. I had no idea what the test was asking, let alone what the answer might be.) My job had been to just proof for format and so on. It had checked out on that. But even allowing that some of the reviewers were checking for other stuff, it's still astounding that with over 25-30 people actually checking for content, no one caught such an obvious error.

After much hand-wringing and discussion of how to rectify for future, management cut the number of people reviewing the examination to five; one each at each distinct step. Because it turned out with 36 people, each reviewer was subconsciously thinking, "I can do this fast because if there was anything, one of the others would have caught it by now." No one could be held responsible because there were too many people to share the blame. But with five checks, one at each stage, someone was specifically responsible for it being perfect at that stage. Actually turned out to work a lot better. Another example of less is more.

So the moral here is, it's better if your editor starts from the assumption that you're an idiot. That way, they'll check everything with obsessive care. Thinking you might actually know something about punctuation, Canadian spelling, consistency and so on just leads to errors.

Friday, August 2, 2013

Currently on my Desk

The first two chapters of the just published The Tattooed Witch by Susan MacGregor (Five Rivers Publishing, July 2013) are available on Susan's site, Suzenyms. I was the editor for the final version of this novel, though another editorial team had already done the initial developmental work on this one, so it was pretty clean when I got it. And of course, Susan is herself a well known editor (with On Spec Magazine), so I imagine it was pretty smooth writing from the get go. Really looking forward to editing the next two books in this series, the second volume of which is already waiting on my desk.

Currently in my "to do" pile:

- have to write the "Afterword" for Leslie Gadallah's The Legend of Sarah (due out Winter 2014)

- final edit on My Life as a Troll by Susan Bohnet (due out Spring 2014

- initial edit on Alicia Hargreaves The Secret Women's Club

- initial edit on Shakespeare for Readers' Theatre, Volume 2 by John Poulsen

- initial edit on The Tatooded Seer by Susan MacGregor

- second volume of Micthell Plested's Mik Murdoch: Boy Superhero series

- initial re-edits on 21 books in the Prime Ministers of Canada series

I also have two solicited manuscripts for review which I can't talk about until/if we sign contracts. And I'm off to When Words Collide convention in Calgary next weekend (August 9-11, 2013) where a number of authors have signed up to pitch books to Five Rivers, so may get one or two more submissions there. (WWC is a great convention for authors and editors: I get more business done there than at any other convention.)

(Okay, not an actual picture of my desk. The actual manuscripts are all Word Files on my computer. Nobody accepts paper manuscripts anymore. But, you know, there's no photo for that.)

So...29 manuscripts currently on my desk, but that's much less of a backlog than usual. With the kids out of school in August and family vacation, probably won't get a lot done until Sept, but this lot should be off my desk by mid-October at the latest.

Oh, and that's not counting the four graduate students I have working on their theses for me. In fact, here is a great Pinterest site by one of my grad students on 400 children's books to aid children through grieving. (Pininterest beats the hell out of asking for a traditional literature review, eh?)

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Acknowledgements

I've downloaded the book out of curiosity, and the next time I'm in a line up at the DMV or similar, I'll read a few pages on my phone. Because I could be wrong; it could be extremely well written.

And the plot could be a lot better than it sounded. I am constantly amazed at how awful people are at writing synopsis or giving verbal pitches. But try describing the plot of, say, Romeo and Juliet without it sounding ridiculous. Can't be done. And I had the interesting experience recently of writing a synopsis for my own novel and my editor telling me, "That's just totally wrong. That's not what your novel is about at all." And am now awaiting feedback from my beta reader, and already know two things: (1) any manuscript always needs a couple of rewrites and (2) after three years of writing, I'm prepared to do another draft or maybe two, and then I'm publishing this sucker if I have to do so myself.

So I sympathize with this writer. Although my general advice is that the positive feedback of friends and family is not a reliable measure of quality or commercial potential, there comes a point where one has invested so much of oneself in a novel that commercial or not, ready or not, it's getting out there.... And that's okay. If you want your friends and family to have a copy of your book, go for it. Mine will have a spaceship on the cover.

The only downside is that if one is trying to become a professional writer, then one runs the risk of hurting one's brand if one publishes a manuscript before it is ready, or publishes an early manuscript before one has achieved professional standards.

And then there's Donal Ryan.

Friday, July 12, 2013

Next Steps

- start on the first chapter of the next novel to keep the momentum going;

- give some thought to possible revisions of the current manuscript—because, let's face it, the first reader is definitely going to identify that it drags a bit in the middle, and that the ending was way too rushed—and;

- prepare for interviews with Shelagh Rogers and Eleanor Wachtel.

My next novel is a parallel-world fantasy, and I am happily composing the opening chapter in my head as I fall asleep each night. I originally outlined this book in 1965, so it's been kicking around in my head for a few years already, so no problem there. (The most innovative aspect of the 1965 outline was that I made the protagonist 64. I was tired of all the 'coming of age' fantasies I was reading and thought, 'hey, why can't it be about an old guy having a coming of retirement adventure'? Of course, no one will see that as inventive now that I am myself approaching retirement age; it will just seem self-indulgent. But what can I do? It's been the same character in my head for 48 years.)

The revisions to the current manuscript I may leave until I get feedback from my first reader, on the off chance he enjoys the pacing of the middle and thought the surprise ending fully developed. No point in indulging in nervous and possibly counter-productive fiddling; though one should jot down any little oversights that come to mind: in my case, checking for gender balance and ethnic diversity, given the novel is supposed to take place in the future. Giving oneself a little breathing space before revisions also allows for perspective.... but one does not want to leave the manuscript alone too long, lest, again, the project loses momentum.

In the meantime, have been spending a lot of my time thinking about the post-launch book interviews. I imagine them going something like this:

Rogers/Wachtel: Did you have any idea that your novel was going to be as successful as it has been? That it would go viral essentially over night?

Runté: I'd like to say that no one was more surprised that I. But the truth is, my wife was considerably more surprised than I. Indeed, I think 'incredulous' comes closest to her reaction.

Rogers/Wachtel: [Laughs]* But you must have had some inkling as you wrote this how it would be received.

Runté: I was quite certain that it would flop commercially. It's strictly 1960s SF, so I thought the audience for it had all died off or at least grown too old to read much any more. I wrote the original outline 39 years ago, so it is pretty primitive SF by today's standards. But I purposely chose the simplest of the 12 novels currently in my head as my first novel, so I could try to master plot and character and pacing and so on before trying to do anything 'deeper'. So it's just a light-weight comedic novel in the style of Harry Harrison's Stainless Steel Rat or Eric Frank Russel's Wasp or maybe even Donald Barr's Space Relations.

Rogers/Wachtel: A lot of the critics are comparing your novel with Bujold's Vorkosigan series.

Runté: That's flattering of course. I am big fan of Bujold. In fact, when I was gearing up for one of my writing retreats, I reread the entire Vorkosiagan saga to get back in the mood. And I freaked at one point because there was this one scene in one of her books that was so reminiscent of one bit I had written that I started to worry that I had remembered it from her book and incorporated it into my novel without realizing.... I accused myself of unconscious plagiarism until I went back and found that scene in the original outline from the seventies, at least a decade before her book had been published, so I was off the hook. But her work has definitely been an influence on me, though I don't see that my work is anywhere as polished or as hard hitting as hers usually is.

And so on. I'd have to talk about my wife being supportive and organizing writer's retreats for me, and so on, to make up for the 'incredulous' line, though it is true she is not a big fan of SF. Except maybe for Connie Willis and Babylon 5. I like both of those too, but you can only cover so much in the interview.

I imagine it's quite an in depth interview, though, so the listener would only get the highlights on the actual program, and would have to go to the podcast for the extended, unedited version.

I'm having more trouble rehearsing my GG Award acceptance speech, because I haven't quite decided whether the book will be nominated for best novel or best YA novel. It could go either way.

*Rogers in particular has a delightful laugh.

I was actually interviewed by Rogers in 1989 about my short story in the first issue of On Spec magazine. She had asked me why I had submitted my story to On Spec and I had replied, "Because no one else would take it," and she had laughed that laugh, and said, "I wish I'd asked you that on-air!" I had, of course, meant that as a speculative fiction story, On Spec had been the right market for it, not that I had bounced it from other markets first (I hadn't) but I heard how that had sounded, and when you get a laugh like that, you just go with it.

Thursday, June 27, 2013

Stephen Fry on Language

I find myself letting a lot of "grammatical errors" go, especially in fiction, so long as the meaning is clear and the sentence doesn't cause me to drop out of the story. I won't force an unnatural sounding phrasing simply to avoid a dangling preposition or split infinitive. Naturally, if I think 'correct' usage will improve the piece, I will suggest it to the author; but if the author has adopted some common usage, I'll go with that because it echoes the reality of the scene the author is referencing and what the audience expects. Forcing "correct" usage in a context where the reader anticipates some common idiom is more likely to drop them out of the story, and so would do a disservice to the text.

I think this approach reflects a less intrusive editorial style than many other editors adopt. I am inclined to give priority to the author's voice, and so tamper only when I believe there is a problem. If I didn't trip over the sentence, I'm not about to rewrite it.

But I have seen other editors who pour over each word of each line seeking ways to improve them. Recently a top author showed me a couple of pages from one of her manuscripts that had a multitude of suggested revisions. I was astounded, because this was an author whose work I almost never find anything to revise. Upon close examination of the suggested edits, I had to concede that in almost every case, the language was subtlety improved. Indeed, I remarked that my novel would greatly benefit from this editor's suggestions, since it was obvious I could learn a lot from how she was tweaking the writing, making it tighter, sharper; both more economical and more effective. But. She was also fundamentally rewriting the author's work, and it really didn't need it. So the author's style is breezy and loose...that's actually part of charm of her canon. As an author with over 30 successful titles out there, reworking the novel to make it more "literary" was perhaps kind of missing the point.

So it is important to understand context. There are certainly many manuscripts that could benefit from a close line by line substantive edit. I could use that editor, for example, because as a relatively novice novelist (in spite of my other writing/editorial experience), I don't have an established following, I don't have a recognizable voice that shouldn't be tampered with, and I likely haven't yet reached my full potential (hope not, anyway!) So I would love to be able to have that editor edit me, both to fix the current manuscript, and to teach me how to write even better next time. Definitely a place for that style of intrusive editing. It's just not what I do.

Not that many of my clients would agree with that assessment for a moment. It is fairly routine for me to demand 400-600 major revisions on a novel manuscript, not counting copy editing of grammar and spelling and so on. But hopefully my suggestions are helping to make the manuscript clearer and more marketable, and not that I am being pedantic.

Thursday, May 16, 2013

The Writer, the Editor, and Human Nature

I have always argued that everyone needs to be edited. No manuscript, no matter how carefully revised by the author, is ready for publication without first undergoing extensive editing by another. All authors are too close to their own manuscripts to catch the logical inconsistencies, or to know what's funny or what works, and what doesn't. I take this as fundamental.

All editors know that when authors bring you their manuscript, they are expecting a few changes, but they are secretly hoping for none, or at least, only the trivial stuff they don't really care about. They are prepared for the editor to change "which" to "that" or "try and" to "try to", but they don't really want the editor to identify the sorts of problems that require one to rewrite whole scenes. When they get the manuscript back covered in blue ink, there are inevitably tears, pulling of hair, and the insertion of pins into small dolls that vaguely resemble the editor.

This is, of course, a normal part of the writing process. Sensible writers know not to respond to the editor for at least a week after they've read and digested the required revisions, because everyone's initial reaction is "What does that idiot know? He's ripping the heart out of my book/article/story!" It is only after one has had an opportunity to review and--reluctantly, grudgingly--accept that the editor might have one or two points worth looking at that one can get down to work on the revisions. Hopefully, if the editor is any good, after having put in the effort to make the suggested revisions, the author comes to appreciate that the manuscript is now even better than it was, and that it was worth the additional effort to get there.

Worst, of course, are the authors who say, "I want you to be brutally honest". Because that is what editors do. It's not about being brutal, it's about fixing the manuscript. So when we hear, "I want you to be brutally honest" we know that this is not a professional, and likely someone who really means, "Please tell me how brilliant my novel is." (I usually ask for money up front when someone says this to me, because I know that by definition I am looking at a dissatisfied customer.)

Which brings us to last Tuesday...when I finally finished my own novel. Of course, it goes without saying that it will have to be edited. And that, like all manuscripts, I can expect my editor to identify any number of necessary revisions.

But um...deep down there is a part of me that really believes that none of that applies to me or my manuscript. Because, after all, I am an editor. With years of experience. And I was revising as I went. So I have already caught that in chapter 27 I had completely forgotten about two of the characters for the last 50 pages. I have already noticed and fixed that character A hadn't actually told B about the secret yet and so B shouldn't be reacting that way. And I've reread this novel like 200 times, and I laugh every single time, so, you know, it works. My editing skills tells me this baby is ready to hit the presses!

So when I hit 'send' to deliver the manuscript to my first reader, what I really expected him to say was something like "Wow, this is brilliant! No need to put in any more work in at all, except perhaps for these 11 words I have identified for you!"

Coincidentally, immediately after sending off my manuscript, I happen to listen to an interview with Five Rivers author Mike Fletcher on Getting Published and am laughing at myself because Mike is saying how he knows intellectually every manuscript has to be edited, and yet how devastated it was to get the editor's critique and how he then had to pick himself up and get to it, etc. And I know, absolutely know, that that is just the way it always is, but still, there is this subconscious voice going,'except of course, my manuscript is perfect'.

And then the interviewer asks Fletcher what three things Fletcher has learned from being edited and he says, "First, that you need to keep your hero under threat; you can't have your characters just sitting around drifting through a scene" and I think, CRAP! That's the middle 1/3 of my book!

And then Fletcher says,"#2, you have to commit, so no 'he was starting to get angry', you have to allow your hero to actually get angry." and I go OH CRAP!!!! I must have written 'started to get angry' like 20 times in just the last six chapters alone!

And Fletcher says, "#3, if your hero says three lines of dialog you have to cut that to two, or maybe one" and I go Oh my god CRAP CRAP CRAP...because that is the entire book...60,000 lines of dialog as hero pontificates to other characters.

And it flashes across my mind that when I was still half-way through the manuscript and gloating how clever all my dialog was, editor Colleen Anderson happened to remark about another book that "there is a difference between your characters saying interesting things, and their doing interesting things", and my thinking...UH-OH!

But I'm sure in my case, having a room full of characters talking in front of a blue screen background for 400 pages will be fine. Really.

Just to be sure that I got a thorough critique, though, I sent my first reader a follow up message assuring him that I needed him to be brutally honest with me.

Thursday, April 18, 2013

The Small Publisher's Point of View

The Publisher/Author Relationship

by James Roy Daley

One reason I signed on with Five Rivers is that the publisher seemed to have a handle on many of these issues and is in it for the long haul. She has steadily grown her business in a business-like way, while many, many others around her have faltered and died. But Daley's depiction of the things that can go wrong if you're not vigilant are absolutely accurate. (My publisher argues that this is more true of old publishing model, and that new POD/ebook model has fewer of these issues.)

It drives me crazy when I read in so many author blogs how publishers are all evil, money-grubbing, rights-grabbing monsters. There are, of course, a number of amateur idiots out there who don't know what they are doing ("Hey guys, let's start a publishing house!") and there are a few big monstrous corporations (run by business boards, rather than editors) that may well be problematic; but most are honest brokers just trying to hold things together. Just as I continually invoke my motto, "The editor is not your enemy", I have to say that in the majority of cases, the publisher is also on your side-- and it would help if you were on his sometimes....

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

The Beginning Poet

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

On Publishing vs Self-Publishing

---Sandra Kasturi, On The Advantages of Small Furry Animals in Publishing, Winnipeg Review

Thursday, February 14, 2013

So You Want to be a Published Author

While I'm on the topic, you may also want to check out the various episodes at Michell Plested's "Get Published" podcast. Quite a few of the episodes provide really useful advice as Michell interviewed various authors, editors, and other experts in his own (successful) quest to get published.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Okay, some demotivational columns worth reading:

Notes from the Drunken Editor: You Are the Joke Here

Nobody gives a F*** that you wrote something

The funny thing about being a development editor is that I can divide most of the authors that cross my desk into one of two categories: highly talented writers who are too shy and (unrealistically) dissatisfied with their work to seek publication (and who need a writing coach mostly for moral support), and aspiring writers who have no idea how bad their work is (who need a writing coach to tell them to go back to the drawing board and never ever let the current manuscript see the light of day). The former are a lot easier to work with, but the latter often do quite well if they can put their egos aside long enough to take the advice they're given; and if they are willing to undertake repeated revisions, not just first drafts. Sadly, many in the second category just shoot the messenger and fail to make any forward motion. Fortunately, most of those will want to design their own covers too, and so effectively warn buyers away from their work (see previous post).

I'm egotistical enough to think I can help any writer get better...but I do occasionally tell writers that they are not sufficiently close to their goal that paying for developmental editing would not be cost effective for them; that they need to go back a couple of steps: perhaps take some writing courses, join a writers' workshop, write two or three other novels, etc, before trying to bring the current manuscript up to publishable standards.

And sometimes our styles/tastes/issues are just too incompatible to be workable. A good development editor doesn't take on clients s/he cannot help, and that is more often about being the wrong genre than about the quality of the writing.

So, I can usually help most SF writers get better. But it helps a lot if the writer starts with a little humility. Thus the demotivational references above. Get a little perspective before demanding that others love your manuscript....

Oh, but don't read those columns if you fall into the first group; that is, someone who worries that their manuscript is not good enough. If you are worried that no one will want to read your book, these guys aren't talking to/about you.

Bad Covers

Of course, authors also have to ensure that if they are going with a small--sometimes even a large--publisher, that the publisher has some idea of what they are doing. Check out the coverart on their other books before you sign on.

On the other hand, I have heard authors complain about perfectly decent covers because they thought the hero's sword needed to be longer or their heroine was brunette not blonde, or some such triviality. So every once in a while we need to remind ourselves just how bad things can get. Here then, examples of cover art so bad they will make you more appreciative of the cover you got, and/or remind you not to use your own clipart cover: http://lousybookcovers.tumblr.com/