Sunday, December 15, 2024

Review of Valdron's Starlost Unauthorized

Saturday, November 16, 2024

Thursday, October 24, 2024

"Alan" Story Reprinted

My mainstream short story, "The Missing Elephant" is up today in CommuterLit. (Free to read)

It was originally published in They Have to Take You In anthology, Ursula Pflug, ed., Hidden Brook Press, 2014 and reprinted in Costal Shelf Issue #1, Nov 20, 2020.

This is an "Alan" story from my series about life in the 1960s, this one about things one did not talk about and the overwhelming power of denial.

Thursday, October 17, 2024

Guest Spot on Re-Creative

Hosts Joe Mahoney and Mark A. Rayner invited me to come on Re-Creative, the podcast about art and writing that inspire writers. I took a long time to think about which writer or artist had had a big impact on me, but they had already talked about Den Valdron's The Mermaid's Tale and Douglas Adams, and I was debating amongst so many other possibilities (Terry Pratchett, Samual Marchbanks, Dave Duncan, Guy Gavriel Kay, Shane Koyzan, Lois McMaster Bujold, etc etc) that I just couldn't focus: until I read R. F. Kuang's Yellowface (See my text review). I could not shut up about how brilliant and relevant Yellowface is, a must-read for every aspiring writer, so that became the natural topic to propose to Mohoney and Rayner.

We also talk about a bit about my writing, editing, and breakfast.

Saturday, September 21, 2024

"Weathering" Reprinted

My short story "Weathering" was reprinted in Daikaiju #19.

https://www.daikaijuzine.org/

"Weathering" originally appeared in Lamplit Underground #4, Sept 2020, pp.12-19.

Thursday, September 19, 2024

Reviews of Kyber and Shared World

Reviews of Kyber by Chadwick Ginther, and Shared World by Ball, Chomichuk, Gillespie and Ginter, Ottawa Review of Books, Sept 15, 2024. Preprint in The N3F Review of Books, July 2024.

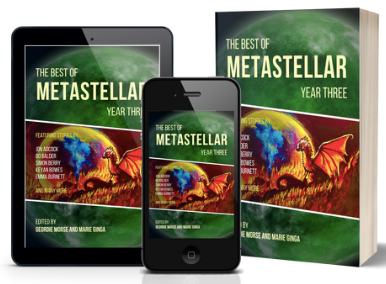

"Inuksuk" Reprinted in Best of Metastellar Year Three

My short story, "Inuksuk",has been reprinted in Best of Metastellar Year 3, September 2024, pp. 60-77.

The story originally appeared in Polar Borealis #15 (June 2020) pp 43-55 and reprinted in Metastellar, May 31, 2023.

Friday, July 26, 2024

Two of My Drabbles Reprinted in Siren's Call #66

Two of my drabbles, "Pillow Talk" and "Pepermints", have been reprinted in Siren's Call #66 Copies of the magazine are free to download at http://www.sirenscallpublications.com/pdfs/SirensCallEZine_Summer2024.pdf

Tuesday, July 16, 2024

Flash Fiction Podcast

My flash fiction "Fami's Watch" was podcast on AntipodeanSF July 14 and is available at: https://antisf.libsyn.com/ My story comes at about minute 6 (intro at minute 5) into the podcast. The story was originally published in Polar Borealis #20 (2021), and reprinted in AntipodeanSF #301 (2023).

Tuesday, July 9, 2024

Two Time Travel Stories Published

My short story, "Sermon on the Mount" and my drabble "Deja Vu" were published in the anthology, A Stich in Space Time: Time Travel Stories, edited by Jay Chakravarti, is out from Culture Pulp Press, July 2024.

"Sermon on the Mount" originally appeared in On Spec Magazine #106, Vol 28 (3) (January, 2018) and "Deja Vu" originally appeared in ScribesMicro #31 (July 15, 2023).

Epub from https://www.lulu.com/shop/jay-chakravarti/a-stitch-in-spacetime/ebook/product-2m5898q.html

Paperback from https://www.lulu.com/shop/jay-chakravarti/a-stitch-in-spacetime/paperback/product-e786k52.html

Friday, June 28, 2024

"Summoning Demons" Out

Saturday, June 15, 2024

Six-Word Story

My review of Guy Immega's Super-Earth Mother

Monday, May 27, 2024

A Review of R.F. Kuang's Yellowface

I have just finished listening to the audiobook of R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface (not to be confused with the novel by Henry Hwang) and I’m completely blown away. It is the most brilliant novel I’ve come across in a decade and the best about writing and publishing ever. Anyone interested in writing or editing or publishing has to go read it, RIGHT NOW--or better yet, listen to the excellent audiobook narration by Helen Laser.

First and most obviously, it’s the most thorough, balanced, nuanced discussion of cultural appropriation and ‘representation’ I have ever come across. Every perspective is covered by at least one character in the novel, so we hear all the arguments, counter arguments, and the often subtle niggling underlying issues that arise to screw up even the most confident proponent of any side. It’s awesome.

But for most of us, all that is secondary to the thorough evisceration of the writing life and the publishing world. It alternates between wincingly funny and painfully accurate. Everything from writer’s block to the maddeningly brutal impact of social media on one’s confidence is laid out in excruciating detail. Every wonderful and painful thing that can happen to one navigating their book through agents, editing, book tours, readings, interviews, and initial sale numbers is laid out. I can’t think of anything that has happened to me as a writer, editor, working for a publisher, or listening to any of my author friends/clients’ anecdotes that doesn’t turn up sooner or later in this novel. If you ever had questions about what happens after you finish your novel, good or bad, this novel lays out what it FEELS like, second by second. Absolutely brilliant!

Maybe a touch discouraging at times, but forewarned is forearmed, eh?

But wait, there’s more!

Yellowface is the best example of the use of an “unreliable narrator” I have ever encountered. I love unreliable narrators and have written/published a bunch of flash stories using the technique myself, but I have NEVER seen a writer able to sustain that for an ENTIRE novel. It is a tour de force performance. The closest I have ever seen before is the classic noir film, Detour, in which our narrator keeps telling us he had no choice but to make the choices he does, even though it’s obvious to the viewers these are really, really bad choices. Yellowface’s protagonist, June Hayward, is similarly inventive in coming up with rationales for her questionable choices, and Kuang convincingly portrays Hayward constantly slipping into believing her own propaganda, how Hayward constantly sees herself as the victim. We have all met people who do this, and I suspect we’re all guilty of it ourselves sometimes, but watching Hayward cycle back and forth between guilt and rationalization is a compelling case study.

Kuang makes Hayward a sympathetic character with whom we can identify, even though she’s being kind of awful. Because we get it. Writing is hard! Publishing is harder! And it’s all totally unfair! One has so little control! We can see why Hayward is more than a little tempted, and how she gets trapped once she starts down her particular road.

How much do you want to read a book on the writing life, publishing, the technique of unreliable narrator and the modern issue of representation/cultural appropriation? What if we threw in, absolutely free, a section on what it’s like to teach writing?

Author Kuang assassinates every mean and useless writing coach any of us have ever had in her portrayal of Hayward’s good intentions versus how the class actually goes. Hayward’s complete lack of self-awareness in her plagiarism of cliched workshop techniques and her shift from mentor to monster is howlingly funny— ‘howling’ because I was wincing the whole time.

[It reminded me of a long-since departed colleague who taught writing workshops for years, even though he had never published a single word in his life, never finished a draft, merely attended so many workshops he was able to reproduce them verbatim. It literally never occurred to him that stealing other people’s exercises is, you know, plagiarism, and that his workshops were entirely inauthentic and inappropriate as he had no personal experience with which to respond to questions. And even real writers can turn mean under the guise of being ‘brutally honest’ with students about their work. (Indeed, I can think of one example where the professor was so damaging, his students so traumatized, that they processed their PTSD by banding together to start a magazine, now in it’s 35th year.)]

Kuang is obviously familiar with such colleagues and finally got the chance to skewer them here. The whole thing is only a single chapter, but nails an entire industry to the wall.

My all-time favourite scene, though, is when Hayward is working with her editor and together they completely undermine the novel Hayward has stolen and now rewritten. The whole point of the original is to represent a little-known historical event through an own-voices account. But the editor pushes Hayward to up the role of the white saviour characters (so ‘readers can better identify’ with the story), and calls for Hayward to downplay some of the crucial cultural elements (that ‘readers won’t care about’). Hayward, of course, has no problem with that at all, believing she is improving an otherwise likely unsalable book. Again, neither character gets the irony of how outrageously racist they are being, how they are destroying the entire purpose of the original. This one very brief scene cuts to the heart of how the lack of representation and the ongoing cultural appropriation remain key components of the industry among legacy publishing. It’s hilarious and gut-wrenching and so accurately portrays the subtleties of the issue, I am left wondering how many readers will miss the scene’s significance entirely.

The whole book is like that: each scene blows up some aspect of writing, publishing, movie options, social media, fickle audiences, families, and cultural portrayals. Kuang is a satirical genius.

But wait, there’s more!

In addition to all these unbeatble themes and insights, Kuang throws in a page-turning, edge of seat narrative, so filled with unanticipated twists and turns that it leaves the reader breathless. Whenever I thought, ‘Oh, well, Kuang has beautifully made the case for ___, there’s no possible response to that’, Kuang switches gears and we meet a character who demonstrates why that argument was full of holes, why this other viewpoint makes perfect sense (at least to those who hold it). Anytime we or the characters start to get comfortable, Kuagn throws them (and us) down a completely new rabbit hole. Each new development pops up out of left field! The only thing we ever know for sure is that things are going to get even worse for June Hayward.

I laugh-groaned out loud at the penultimate resolution because it was completely, outrageously believable, but then Kuang threw that one out as well and pushes us to the very edge. No spy thriller could come as close to making my head spin as did Yellowface.

In the end, we as readers are left questioning everything we thought we knew about publishing, and more importantly, questioning every decision we have ever made about which books are worthy of our attention, why we actually choose to read what we read.

Act now, and for no more than the price of the hardcover, you can receive the audiobook voiced by Hellen Laser. Seriously, I recommend Laser’s performance over trying to read this yourself. Laser gets every nuance, every subtlety of Kuang’s purpose and carries the listener along past the bits were I might have been tempted to put a print copy down as 'too much' to cope with. One can’t “Yes, but...” the text if it is being spoken and the speaker just carries on.

My apologies to readers who are too young or not Canadian and may not be familiar with the ‘but wait’ format of the old K-Tel ads. I wanted to portray the same level of excitement, if not the dubious quality of most infomercial products

I confess that parts of the novel came a bit close to home for me, as following the passing of the late, great Dave Duncan, I have half a dozen of his partial manuscripts on my desktop to finish, though I came by them honestly. And I have run a lot of writing workshops/courses in my day and have been guilty of advising authors to take or add in this or that element (though not cultural ones, I don’t think) if they wished to increase the book’s commercial potential. I have even confronted own-voices issues of including trans themes or characters not of my culture in my own writing. Reading Kuang has helped me articulate what I’ve been trying to say on these matters in a more articulate way, and appreciate the way Kuang has shown that none of these have clear cut lines.

Though clearer than June Hayward believes....

Friday, May 17, 2024

Review of S.W. Mayse's Shadow Matter

My review of Shadow Matter is now up at Ottawa Review of Books.

Tuesday, May 14, 2024

Fred Gambino's Dark Shepard Launched

Fred Gambino’s first novel, Dark Shepard, launched May 14th from the award-winning UK publisher, Newcon Press. Dark Shepard, the novel, is not to be confused with The Art of Fred Gambino: Dark Shepard, his 2014 art book from Titan Books. (Fred is a famous book cover artist and Hollywood/game conceptual designer and has been working on the Dark Shepard universe for decades.) The book is brilliant and the most cinematic novel I’ve ever edited&emdash;if somebody doesn’t pick this up as the next movie franchise, they’re missing a sure thing. I mean, he’s already done the movie trailers:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aettbKa5sws

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tmvq3pSx1Xs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VpCVSleFd4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwjFhaQ5tx8

Wednesday, May 8, 2024

Book Launch of Dave Duncan's The Traitor's Son

May 7, 2024 was the official launch of the late great Dave Duncan's novel, The Traitor's Son, which I edited and shepherded through to publication on his behalf.

The Traitor’s Son is one of Dave’s few science fiction novels, and his most political. It’s about a narcissistic leadership that knows the (distant colony) world is dying but hopes not in their lifetimes and continues to ignore the problem for their personal enrichment. It’s a pretty obvious allegory, but wrapped in a daring-do adventure novel.

It’s also about people’s assumptions about inherited identities and how that can be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The launch was held in Calgary in the 300+ seat Patricia A. Whelan Performance Hall in the main branch of the public library.

The launch was from publisher Edward Willtett's Shadowpaw Press, and organized by Robert J. Sawyer, whose trade paperback edition of The Downloaded is similarly from Shadowpaw. Sawyer was kind enough to share his launch with Duncan's. Turn out was good (especially given the terrible weather that day).I reviewed The Downloaded for The Ottawa Review of Books. Given I was the editor on The Traitor's Son I can't really review it for ORB but can say here I thought it up to Duncan's usual high standards.

Duncan's next book, Corridor to Nightmare will launch Saturday, August 17, at Calgary's When Words Collide convention.

Sunday, May 5, 2024

Another Flash Fiction Published

My flash fiction, "Garbage In, Garbage Out", was published in the Summer 2024 issue of Sci-fi Lampoon (May 5, 2024). It is another in my series about Fami and his AI Watch.

Thursday, May 2, 2024

No One Buys Books

https://www.elysian.press/p/no-one-buys-books?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

Monday, April 22, 2024

My Poem Reprinted

My poem, "Memory Loss" has been reprinted in the Fragments of Lost Time collection from Dark Thirty Poetry Publishing (Adam Shove).

"Memory Loss" is my only serious poem so far, so am pleased to see it given new breath in this collection.

Wednesday, April 17, 2024

Review of Robert J. Sawyer's The Downloaded (and other books)

Sawyer writes the purest form of science fiction in which he either takes current trends and extrapolates their long-term implications, or comes up with completely unique, sometimes jaw-dropping ideas and then works through their most subtle ramifications. His novel and subsequent TV series, Flashforward, for example, presents the premise that everyone on Earth simultaneously gets a two-minute glimpse of what they are doing in the near future. What do you do to comprehend, embrace, or avoid the future you just saw? Can the future be changed, or is knowing what happens what creates that future? Flashforward is every time travel paradox story ever, but inverted, so instead of risking changes by some meddling explorer going back in time, everyone is moving forward together. Sawyer's analysis is both deeply philosophical and character-driven. Told through the personal journeys of its characters, the novel is a fast-action read, but leaves you with questions about destiny and self-determination for years after.

Or, take my personal favourites, The Quintaglio Ascension trilogy, in which Sawyer examines the sociological impacts of Galileo, Darwin, Freud by following their equivalent breakthroughs in the evolution of an alien civilization. It is a thought experiment of extraordinary subtly that allows us to acknowledge the role of great thinkers and key paradigm shifts within our own culture. One of Sawyer's earliest series, I still highly recommend it.

And if you enjoyed the Oppenheimer movie, reading Sawyer's The Oppenheimer Alternative, is a must-read.

His latest release, The Downloaded, is similarly thought-provoking as Sawyer combines a bunch of unrelated future scenarios,

The initial premise is that astronauts have been uploaded to separate virtual worlds while their bodies remain in cryonic suspension for years as their starship travels the immense distance to another star. Downloaded back into their bodies, they discover that things have not gone exactly as planned. That's only the first of a half dozen major twists, but my "no spoiler" policy means I can say no more. As with Flashforward, the book has an array of character studies, philosophical and moral issues to grapple with, and the underlying theme of what choices one would make in the characters' shoes.

Almost as fascinating are the implications of Sawyer's choices for the publication of The Downloaded. Sawyer has always been in demand on TV and radio as a commentator on any and all future trends. He is a popular keynote speaker at writing conventions as an industry insider and a master of social media and marketing. Where he leads, many authors follow. So it was with special interest that we saw The Downloaded first released as an audiobook exclusive from Audible.

Audiobooks have been steadily increasing in popularity and market share, so it's no surprise that Audible (the largest player in the industry) approaches some of the top commercial authors, not just for their books, but to bring them out first and as full play productions. Audible's The Downloaded stars some top Canadian talent—Brendan Fraser, Luke Kirby, Vanessa Sears, Colm Feore, Andrew Phung—and is a compelling drama. I like to listen to audiobooks as I do household chores; The Downloaded was so edge-of-the-seat, I found myself actively looking for chores to take on, so I could keep listening.

Further, while many authors would sell their souls for a contract with one of the Big Five publishers, Sawyer—and increasingly other big-name authors—have been turning their back on these corporate publishers for smaller regional presses for their print editions, and self-publishing their own e-book editions. The print version of The Downloaded is therefore being released this May by Shadowpaw Press, a relatively new regional press from Saskatchewan founded by SF author, Edward Willett.

I confess, I haven't actually read the print version, but base this review on the audiobook. I understand there are minor adaptations in the audio version to make the story workable in play format, though the story is obviously fundamentally the same, and I have no hesitation recommending them both on that basis. If you have chores to do, check out the audiobook; if you want the authentic reading experience, The Downloaded is available now for pre-order from the usual outlets. Then, well, there are 25 other Robert J. Sawyer books to enjoy in e-book, print, or audiobook.

Tuesday, April 16, 2024

Review of The Lost Expedition

The Lost Expedition is the third and final volume in the Dream Rider trilogy. The first two novels, (The Hollow Boys, reviewed in ORB November 2022, and The Crystal Key, reviewed May 2023) were wildly successful, garnering critical acclaim including an Aurora Award and a juried IPA award. If you haven’t already read the first two Dream Rider books, you need to start there; if you’re already read those, I won’t need to sell you on this one because you will have already been waiting for answers and lined up for this one.

The story concerns rich comic artist,18-year-old Will; his street-wise girl-friend, Chase; and her kid brother, Fader. All three have mysterious but limited powers that have allowed them to enter dreams and move between the worlds of the multiverse, battling an as yet unidentified villain or power. The central mystery is to find out what happened eight years ago that caused their parents to go missing, and their powers to manifest. Thus, the search for the lost expedition.

I compared the first volume to a superhero comic or a graphic novel—sans graphics; I compared the second to the thrill of a 1950s movie serial, once a regular part of Saturday matinées. This time, The Lost Expedition put me in mind of A Wrinkle in Time. Both books are about the conflict between order and chaos, both place unreasonable demands on their young protagonists, both have the same sweeping scope that engages one’s sense of wonder. Evoking the same emotional response, The Lost Expedition took me back sixty years to the exact weekend I discovered A Wrinkle in Time and the forgotten memory of reading in the dark after lights out.

Looking back as an adult, though, I far prefer Smith’s world building and politics to Madeleine L’Engle’s. Smith has written a series that is far more inclusive and far less elitist than L’Engle’s. Smith’s characters represent different social classes, ethnicities, abilities and weaknesses. The Dream Rider series is targeted to today’s modern YA audience and so better suited to current sensibilities. Whoever reads this book will find at least one POV character with whom they can identify.

Which is not to say The Lost Expedition doesn’t have a few flaws. I was annoyed and distracted early on by a logical flaw in the plot, only partially mitigated by the characters recognizing that inconsistency themselves twenty pages on, and that was therefore an important clue. I was similarly annoyed that one of the characters, Nix, can only remember key facts when it is time for the next clue to be handed out—again, somewhat mitigated by a reasonable explanation in the denouement. Withholding key information from the reader in a mystery feels like a bit of a cheat, even though Smith eventually explains why and the reader has to grudgingly admit it all makes sense. Still, waiting until the end to explain everything from all three books in the final chapters of this one meant the denouement went on a bit too long after the grand climax. Indeed, there are several occasions throughout the novel when the characters get bogged down explaining things to each other while the action grinds to a stop.

Notwithstanding these minor reservations, The Lost Expedition is a solid ending to a great series. The various mysteries are finally revealed in all their intricate complexity; there are several twists I totally did not see coming; and there is a sweeping majesty to the world building we have not seen since—well, since A Wrinkle in Time.

Marathoning all three books at once is probably best, so that one can keep all the fiddly bits of the mystery in mind and so that the denouement in book three becomes proportionate to the series as a whole. If you haven’t done so already, you should package up all three volumes to gift to any young adults in your life—or any adult in your circle nostalgic for the Golden Age of science fiction fantasy.

The Lost Expedition is published by Spiral Path Books.

This review originally appeared on The Ottawa Review of Books.

Monday, April 15, 2024

"Exit Duty" Republished on Short Story Substack

My shot story, "Exit Duty" was reprinted on Short Story Substack today.

"Exit Duty" originally appeared in the William and Mary Review, a university literary magazine so I am very pleased to see it now available to a wider audience.

Saturday, April 13, 2024

Keynote Address at WordBridge 2024

I was honoured to be one of two keynote speakers at the 2024 WordBridge Writers Conferencce in Lethbridge Alberta. I was asked to speak to the theme "Home/Writing From the Heart" so talked about building a writing community in Lethbridge, the advantage of choosing a smaller Canadian regional publisher over going for the Big 5, and writing authentically.

Thursday, April 11, 2024

"Crossing Avenue" Reprinted Online

My flash fiction, "Crossing Avenue", was published by Stupefying Stories and is available for free online.

The story originally appeared in the literary magazine Meat for Tea:The Valley Review Vol. 14 #1, 2020; and was reprinted in Polar Borealis #Dec 2022, pp31-32.

Thursday, April 4, 2024

"Disposable" Reprinted

Monday, April 1, 2024

New Flash Fiction Published

Monday, March 18, 2024

Review of The Year's Best Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction Vol 1.

When John Robert Columbo came out with the first anthology of Canadian speculative fiction, Other Canadas, in 1979, it was the first time most of us realized that there even was a Canadian version of the genre. To cobble the collection together, however, Columbo had to scour all of history and pad the list with the likes of Cyrano de Bergerac and Jules Verne—non-Canadians who happen to have set a story in the polar north—to fill his pages. By 1985, the field had expanded sufficiently that Judith Merril was able to solicit enough contemporary Canadian SF to fill the first Tesseracts anthology.

When I co-edited the fifth Tesseract anthology over a decade later, we had over 400 submissions, and I confidently predicted further explosive growth for Canadian SF&F. The Tesseract series is now up to number 22 though the series has morphed into themed anthologies rather than a general survey of the Canadian genre. Imaginarium 2012 was the first attempt at reprinting the “Year’s Best” but the series ended with Imaginarium 4. We therefore have lacked a “Best of Canadian SF&F” series for the last eight years.

Enter Stephen Kotowych, the editor of the Year’s Best Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction, Vol.1 (2023).

If I thought working on Tesseracts 5 was challenging, I cannot begin to imagine trying to keep on top of a field that has expanded continuously over the last thirty years. The undertaking, especially by a single individual rather than a team backed by an established publisher, is outrageously audacious. And yet, Kotowych seems to have pulled it off. With 37 entries from 24 different magazines and 6 anthologies—a total of thirty different venues—the collection is certainly a representative survey of the field. The stories range from hard science fiction through fantasy, horror, and fevered dreams to pure CanLit. Inevitably, as with any anthology, tastes differ and one might quibble whether this or that entry is the “best” Canadians have to offer, but there’s no question Kotowych has nailed the breadth of what’s out there. Story quality ranged from “solid” to “outstanding” with the overall weighting tipped heavily towards the “excellent” end. If I’m honest, I think this collection is better than the one I co-edited, a reflection of how Canadian speculative fiction has expanded and matured in the decades since.

Best of all, the collection introduced me to a number of authors with whom I had not previously been acquainted. How had I missed, for example, Suyi Davies Okungbowa? I was shocked to find a stack of novels by this University of Ottawa prof, whose “Choke” is one of the outstanding stories in the current collection. That one discovery is worth the price of the collection five times over. Although “Choke” feels as if it would be comfortable in any CanLit magazine, it originally appeared in Tor.Com, so legitimately qualifies as speculative fiction. But wow! The freshness of the phrasing, the passion of the writing, the absolute resonance of the contemporary experience just floored me. That’s six new novels added to my To-Be-Read pile right there.

Similarly, I had no idea Nebula-nominated Ai Jiang was Canadian. Her “Give me English” is a great opening to the anthology, not just because it’s a gem of a story, but because it nicely illustrates how the current generation is infusing fresh themes and viewpoints into the Canadian genre. I have banged on for years how Canadian SF differed from that of the American (and to a lesser extent, the British) mass market SF&F, but I have to concede that the (English-language) Canadian genre often lacked culturally diverse voices, beyond some influences from Quebec. Jaing’s story speaks not just to the immigrant experience, but to the post-colonial, anti-capitalist themes that have become a natural part of the SF scene. Chelsea Vovel’s “Mischif Man” story of a Métis superhero similarly takes on Settler colonialism, and Lavigne’s “Choose Your Own” is one of the best feminist pieces ever: wincingly on target.

These and the majority of the entries fit my argument that Canadian speculative fiction is oddly optimistic despite the often downbeat premises. The future is on fire in Premee Mohamed’s “All that Burns Unseen”; perpetual war and exploitation are central to Michelle Tang’s “Vihum Heal”; oppressive religion stifles life in Kate Hearfield’s “And in the Arcade”; Charlotte Ashley’s “Distant Skies” features capitalist manipulation of our destinies through genetics; Holly Schofield’s “Maximum Efficiency” has robot soldiers vs humans; KT Brysk’s “Folk Hero Motifs in Tales Told by the Dead” is set in hell, for heaven’s sake. And yet, life goes on and people (or other sentients) find a way. I love this approach of ordinary people bumbling through tough times to carve out acceptable outcomes. It is the literature we need amidst the dumpster fire we’re living through.

Reynold’s “Broken Vow: The Adventures of Flick Gibson, Intergalactic Videographer” provides some needed comic relief, and the fiction is broken up by the inclusion of nine rather good, accessible poems.

Overall, it is a great collection, a great reflection on what Canadian speculative fiction has to offer, and a great first entry in which one can only hope will continue as an annual series.

The Year’s Best Canadian Fantasy and Science Fiction Vol.1 (2023) is published by Ansible Press.

Wednesday, February 28, 2024

Al/ice Reprinted

My short story "Al/ice" has been reprinted in the Queens in Wonderland anthology from No Bad Books.

The story was originally published in Shoreline of Infinity #21 (April 2021), which provided a really helpful sensitivity read.Wednesday, February 21, 2024

Detour on the Eight-Fold Path

"

"The story originally appeared in Neo-Opsis Magazine #31.

Tuesday, February 20, 2024

The Changeling and the Bully" Reprinted

Polar Borealis is available as a free PDF download from https://polarborealis.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/POLAR-BOREALIS-28-January-2024.pdf

This is the origin story for my Ransom and Friends urban fantasy series. The story was originally originally published in Mythic #17, Oct, 2021, pp. 65-74.

Monday, January 15, 2024

Review of State of the Arc

This review originally appeared in The Ottawa Review of Books, Nov 2023.

State of the Ark: Canadian Future Fiction

Edited and Introduction by Lesley Choyce

Reviewed by Robert Runté

As soon as I heard about this anthology, I knew I had to have it for my collection, because I already have Lesley Choyce’s and John Bell’s pioneering 1981 Visions from the Edge, the first anthology of speculative fiction from Atlantic Canada; and Choyce’s 1992 Ark of Ice, a now classic anthology of Canadian speculative fiction (Canada being the ark in question). State of the Ark represents the current state and range of speculative fiction in Canada 2023, including checking in with some of the same authors from the 1992 volume. It is, like its predecessors, an excellent cross-section of the Canadian speculative genre at one moment in time.

At one end of the spectrum, we have traditional space fiction: Robert Sawyer’s “Star Light, Star Bright”, is an approachable story of Dyson spheres, interstellar colonies, and good parenting. Sawyer’s stories are always about exploring the less-than-obvious implications of big scientific concepts and bringing those down to the human level. This short is an example of why Sawyer is arguably Canada’s most successful science fiction writer.

Julie E. Czerneda’s “Foster Earth” is similarly a classic first-contact story: humans trying to figure out how to communicate with The Silent with absolutely nothing to go on . . . and coincidentally, another story about great parenting. I love it!

My favourite SF story, though, is Julian Mortimer Smith’s “Read-Only Memory”, which explores near-future tech to absolutely nail contemporary attitudes and relationships. I’m definitely going to have to hunt down more of Smith’s work.

Jeremy Hull’s “Bright Future” covers the similar ground of virtual technology and relationships, but this time from a parenting angle (hmm, starting to see a trend here). C.J. Lavigne’s “Side Effects May Include” is a sharply Canadian take on medical tech’s relationship with late-stage capitalism.

Other more or less traditional SF entries included Spider Robinson’s story of slow interstellar travel; John Park’s “Hammerhead” other-world colonization; Terri Favro’s “Winter Pilgrimage of the Storytellers”, a multi-world portal novel; and Hugh A.D. Spencer’s “Shoebox or The End of Civilization in Five Objects or Less”, a delightful satire of pompous museum staff, the ill-treatment of freelances, and the comeuppance Spencer (himself, a museum consultant) would wish upon them. Greg Bechtel’s “2115: Notes Toward Nine Stories of the Future” examines recent articles to project nine mutually exclusive punchlines for future fiction.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have the stories that lean heavily into CanLit, like Katherine Govier’s “VIXEN, SWAN, EMU, BEAR”. I really enjoyed her writing which connected each totem to moments in the narrator’s relationships. This story could comfortably have found a home in any Canadian literary journal. If anything, I questioned whether the speculative element was a bit thin, really only appearing in the last page—it felt a little tacked on. I was, therefore, not entirely surprised to read in her bio that the story had indeed originally appeared in Exile Literary Quarterly and the ending was added for this volume. I am not complaining though! It’s a marvelous piece of writing, and I am always appreciative that our best literary writers are open to stepping across genre lines, which elsewhere are often considered impenetrable. The number and influence of Canadian literary writers crossing over into speculative fiction is one reason our version of the genre is distinct from the mass market American version.

Between these two poles are stories that blur the line between literary and speculative genres.

Élisabeth Vonarburg’s “Terminus” is a parallel world story, but mostly about relationships, identity and self-worth. Casey June Wolf’s “Substance. Light” works some of the same themes, but with an even more poetic bent. Both allude to suicide (so: trigger warning).

Candas Jane Dorsey’s “The Card is the World” a dark--or maybe darkly funny--story plays with literary structure to deliver a commentary on science, suits, and--inevitably--relationships. (And almost as an aside, the invisibility of older women.) Tim Wynne-Jones’ “Eternity Leave” has flying saucers, but it is really a story about imagination, the literary life, and a beautiful day. The story nicely balances literal narrative and Wynne-Jones’ whimsical style.

Lesley Choyce’s own “Tantramar: A Love Story in a Time of Crisis” is either speculative fiction if we believe the characters, Canlit if they are delusional. It could go either way, but it works as a love story, so is categorization important?

I judge The State of the Ark an accurate presentation of current trends in the genre. Old writers and new are both represented, the new bringing a hopefully growing diversity of voices. There is an underlying optimism running through all these stories, even the dystopian ones, which is perhaps new. The collection as a whole is more literary than idea-driven, more about the writing than story-telling, which I would argue reflects the growing maturity of the speculative genre overall, even beyond Canada. Better yet, the majority of the stories here straddle these divides to combine the best of both CanLit and SF. There is room for both space ships and poetic language in Canadian speculative fiction, and even the straight-forward SF all has an identifiable Canadian slant to it.

The State of the Ark is a ‘must-have’ for anyone wondering what Canadian future fiction fares these days.

The State of the Ark is published by Pottersfield Press, 2023.